Speaking about Faith and Life Abroad – An Interview with Protopriest Peter Perekrestov

“I Would not Want the Russian Church Abroad to Lose Its Identity” – Protopriest Peter Perekrestov:

You were born and reared in the Russian diaspora. Tell us about the people who influenced you in your younger years and nurtured in you a love for the Church and your historic homeland.

– I was born in Montreal, Canada. My father’s father was an officer in the White Army born in Yugoslavia (he was killed by the Reds in 1945), and my mother was evacuated by the Germans from the Soviet Union when she was 13 years old—her father was a regular soldier in the Red Army and disappeared without a trace. The Russian language was the only one used in our home, and when I started school, I didn’t speak a word of English. We often had Russian visitors, including, when possible, people from Soviet Russia, which was a rarity in those days. I remember 1967, when Montreal hosted the International Expo, and the Soviet Union had a huge pavilion and accompanying delegation. Over the summer we visited the expo every week, attended concerts, and we always had Russian guests come visit.

On Saturdays, my brother and I attended Pushkin Russian School, and on Sundays we served as altar boys at St Nicholas Cathedral; in fact, we’d arrive early to participate in the greeting of the bishop; it was far—we had to take the metro and two buses. The parish rector was Archbishop Vitaly (Oustinov), the clergy consisted of monastics, we had no “white clergy” at the cathedral. We were accustomed to it being silent in the altar, with no idle chatter—it was a very pious atmosphere.

Despite the fact that we grew up in Canada, we had a sort of microcosm of Russia: church life, Russian school, our friends were exclusively Russian, we went to concerts of Russian music (when musicians were on tour), and participated in Russian-school performances. We didn’t consider ourselves Russian-Canadians or Canadians of Russian descent—we were Russians, with a corresponding world view.

You said that monastics served at your church. This probably affected your spiritual upbringing, and the fact that you decided on a priestly career.

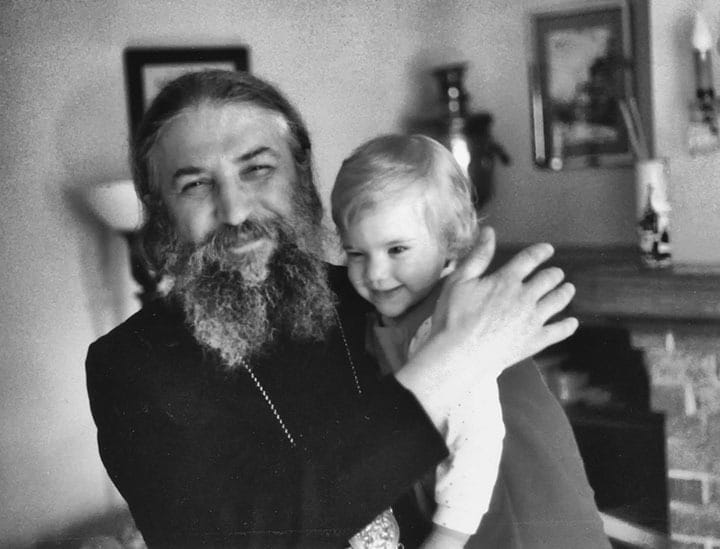

– Well, to be honest, I am still crawling, spiritually speaking, not even on all fours yet, though I had quite a few astounding examples of how to lead a spiritual life. I really did grow up in a parish led by monastics, but I really had no idea of the way of life in a monastery when I was growing up. I first visited a monastery in 1972, when I was 16 years old. Our kind Archimandrite Feodor (Golitzin) loved young people, he owned a minivan and always arranged for trips for us—to Transfiguration Skete in Mansonville, to the zoo, to the town of Rawdon which had a chapel dedicated to the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God.

One day, Fr Feodor invited me on a youth trip to Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, NY. It was a fateful trip for me in terms of deciding on my life’s path. I remember every moment: how we approached the monastery on a foggy evening, how monks and seminarians emerged from the church and went to the refectory, how they sang a prayer before dinner. I remember the singing on the kliros, the magnificence of the monastery church, the decorum of divine services, and the hospitable and joyful faces I saw there. I was amazed at all of this. During lunch, one simple monk, Fr Prokopy, asked my name and said: “Come to us this summer.” I took these words to heart.

Upon returning to Montreal, I stopped watching TV, I didn’t miss a single vigil service, even when public transportation was halted due to snow. I constantly listened to recordings of monastic services. Mama was frightened that I would become a monk!

I spent the summer of 1972 at the monastery and decided after my second year at university that I would bind my life to the monastery and seminary. Of course, I still had not made the conscious decision to enter the priesthood. In 1974, I enrolled at Holy Trinity Seminary.

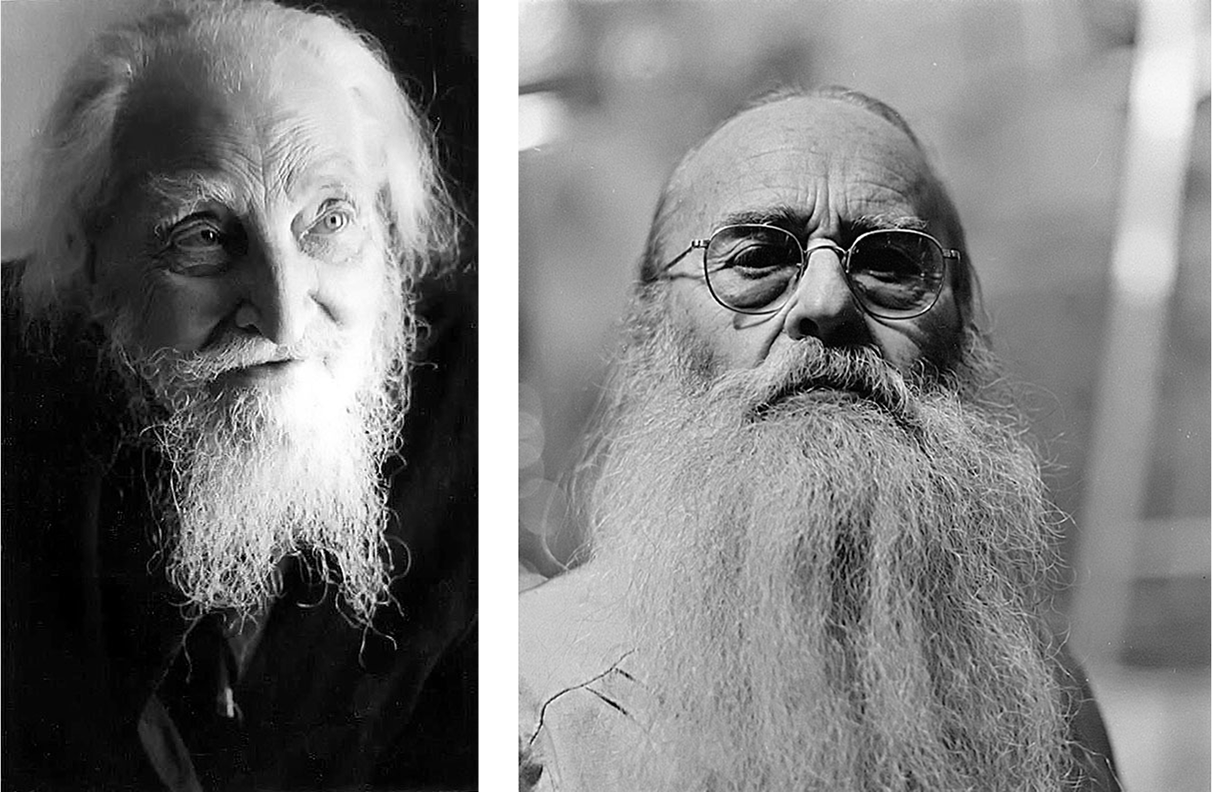

My spiritual and ecclesiastical education was without a doubt connected with the monastery. In those days, the brethren of Holy Trinity Monastery were remarkable—these were people who had endured a great deal in their lives, they survived the Revolution, the Soviet terror, World War II, concentration camps, hunger, the poverty of life as a refugee. There were many simple monks from the peasant stock. But there were also people of culture, of great intellect, for instance, Archbishop Averky (Taushev), Archimandrite Konstantin (Zaitsev) and Archimandrite Kiprian (Pyzhov).

The latter was my spiritual father, and my obedience was to serve as his driver. He tried to instill in me a taste for icon-painting, church adornment, a sense of beauty and harmony, and he also corrected the many grammatical errors in Russian that we seminarians made. Also, once a week, I would drive the teacher of dogmatic theology to the seminary, Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky, to an old-age home, where his ailing matushka lived. His wise and reassuring words on theological topics during these drives were unforgettable.

Over the course of four years I never witnessed any quarrels or harsh words in the seminary or monastery among the brethren, never heard any insults or complaints, either in the monastery or seminary. During those years, the people there didn’t need to be told what to do, they didn’t need oversight. They performed their monastic duties, they followed the example of their abbot, Archbishop Laurus (the future First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia). In addition to the spirit of love and faith that reigned at the monastery, I must also mention the spirit of freedom and trust in the seminary. Of course, in the life of the Church, you can force people to observe administrative discipline out of fear, but this wouldn’t so much be a family of Christ as a factory of some sort. In a real Church family, there must be trust and love, and love is always free and is never forced.

I will remember by years in the monastery for my whole life. When graduates of Holy Trinity Seminary of that period gather, we tell endless stories about the monks, the teachers, they were genuine ascetics who expended all their efforts and were paid peanuts for it. We could easily put together 12 volumes of a Jordanville version of the book Everyday Saints, one for every month of the year!

You got to know hierarchs of the “old school,” those who were educated in pre-Revolutionary Russia, those who experience persecution. Who made the greatest impression on you and your classmates?

– Once during a diocesan pastoral retreat, Fr Alexander Lebedeff (now a protopresbyter) of Los Angeles remembered the hierarchs of blessed memory of the Russian Church Abroad: “You know, father, if you think about it, you could probably canonize as a saint half of the bishops of the Church Abroad.” And he’s right: our generation witnessed so much sanctity that words cannot express it. In the history of the Russian Church Abroad, there were three times that a bishop was disinterred—St John (Maximovich), before his canonization; Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky) and Bishop Konstantin (Essensky), the remains of whom were all uncorrupt!

The hierarchs of the Church Abroad all lived very modestly, sharing the plight of the other refugees. They did not own expensive cars, they had no entourages of acolytes, personal secretaries, cooks, they did not enjoy earthly fame and influence. One need only remember Archbishop Nikon (Rklitsky), the author of the monumental 17-volume Life of Blessed Metropolitan Anthony (Khrapovitsky) of Kiev and Galicia, who lived in the attic of a church house in one of the worst neighborhoods of New York City. But these bishops were spiritually wealthy, they had great moral authority. Their entire lives were dedicated to serving God, neighbor and Homeland.

Speaking of hierarchs who made a great impression on me, those would be Metropolitan Laurus (Shkurla) and Archbishop Anthony (Medvedev), the latter having been my ruling bishop and cathedral rector for the first 20 years of my priesthood. I met the future Metropolitan Laurus when I was 15 years old, in Montreal in 1971. The Council of Bishops of the Russian Church Abroad convened there at the time. My brother and I served as acolytes at Liturgy and saw the largest gathering of bishops we had ever seen. My brother told our grandmother about it, and she decided to invite a group of the bishops for dinner, and one evening, after a session of the Council, six or seven bishops came to visit. I remember that the most talkative and loudest was Archbishop Seraphim (Ivanov) of Chicago, and I remember Archbishop Antony (Bartoshevich) of Geneva.

The quietest was the youngest and most junior hierarch, Bishop Laurus of Manhattan. He didn’t speak a word during dinner, and impressed me as the humblest of all monks. Still, after dinner, my brother and I and the young cell-attendant of Vladyka Laurus, Paul Loukianoff (now Archbishop Peter of Chicago), had a conversation on the second floor of the house, when suddenly Vladyka Laurus walked in and started a conversation with us.

Thank God, this tradition of accessibility by the bishops of the Russian Church Abroad has survived, even on the level of our First Hierarch, Metropolitan Hilarion.

It was Vladyka Laurus himself who later ordained me a reader and subdeacon, then to the diaconate and priesthood. During my years as a seminarian, I served as a subdeacon with him. Later, after 2000, he entrusted me with authoring several church texts.

These archpastors—Vladyka Laurus and Vladyka Anthony, had an unbelievable sensitivity to liturgics, a living conception of divine service—on one hand, an ancient, unchanging one, and on the other—a renewable and living one. They taught me the spiritual aspect of church life, how the mechanism of church cooperation and collegiality works. With regard to conciliarity and church order, they adhered strictly to the spiritual legacy of Metropolitan Anastassy (Gribanovsky) of blessed memory, as it relates to the 34th Apostolic Canon* as the cornerstone of establishing relations between a senior hierarch and his brother bishops. I consider these bishops not only my spiritual guides but fathers as well. I often turn to them with the request to pray for me before the Divine altar, to offer me guidance and wisdom in difficult questions and circumstances.

In the 1990’s, you started to visit Russia and contact clergymen of the Russian Church in the Homeland. Tell us about your impressions, about the people you met. How did they react to you?

– I first visited Russia in December, 1989. It was an unexpected trip—I never thought that I would ever travel to my homeland, and it is naturally difficult to express what I felt at the moment. My first contacts there were mostly with clergymen whose positions were similar to those of the Church Abroad with regard to the veneration of the New Martyrs, the Royal Martyrs, with those who considered the Revolution and all of its consequences not so much as a continuation of Russian history as a profound catastrophe, an historical fracture.

Some of them strove to go under the omophorion of the Russian Church Abroad. Time showed us that some had good intentions, while others sought personal gain or were just passers-by, if not actual provocateurs. Honestly, we were naïve then, we didn’t understand life in the Soviet Union, including Church life. Still, we were obliged to proceed on that path. I think that thanks to the experience, even to the mistakes that we made, we were in fact sometimes led astray, that by the year 2000 we came to understand the real situation in Church life in Russia. We embarked on the path to reestablishing ecclesiastical unity without any illusions, but soberly and with sound judgement.

We were viewed in different ways be the people of Russia. For some we represented their “ticket abroad,” or a source of humanitarian aid. For others we were real Russians, the heirs of the pre-Revolutionary, exiled Russia. For others still we were foreigners, ideological foes. But usually, after we got to know each other better, even those who were very wary of us changed their opinion. We became, if not friends, then at least fellow-warriors for Christ, people who loved the Church and our Homeland.

Among the clergymen I became close with in the 1990’s, with whom I maintained contact for many years, were Protopriest Lev Lebedev of Kursk, Protopriest Anatoly Yakovin from the town of Velikodvoriye in the Gus-Khrustal region of Vladimir oblast, Protopriest Mikhail Zhenochin from Gdov in Pskov oblast and Protopriest Vasily Ermakov of St Petersburg.